Sometimes the ideas of (co)limits and subcategories don’t really play nicely with each other. A (co)limit of a diagram in a category has two basic pieces. One is an object of the category which people usually think of as being the “result” of taking the (co)limit. The other is a (co)cone, which is a bunch of maps between the objects of diagram and the (co)limit object such that everything commutes. So a subcategory has two different ways it can screw up a particular (co)limit (assuming the whole diagram is in the subcategory): by not having the (co)limit object, or by not having all the maps in the (co)limiting (co)cone. If C’ is a subcategory of C, and D is a diagram in C’ such that the (co)limit of D exists in C, call it X, and the (co)limit of D exists in C’, call it Y (they don’t have to be the same), then the universal property gives a unique morphism of C between X and Y (X to Y for limits, Y to X for colimits) making everything commute. I’ll describe a few specific examples that I’ve used.

Bijections

First, an example of how the arrows can get messed up. Consider the category FinSet with finite sets for objects and functions for morphisms. It has all coproducts (colimit of any pair-of-objects diagram) given by disjoint union and inclusion maps.

Now consider the wide subcategory FB FinSet of finite sets and bijections. For any pair of finite sets A and B, A+B is still a finite set, and thus still in this category. However, if neither happen to be the empty set, then the inclusion maps are not bijections, and thus not in this category. This still defines a symmetric monoidal structure on FB though, just not cocartesian. In fact, + restricted to FB is equivalent to the free symmetric monoidal category on one generator, also called the symmetric groupoid. We used this category in the definition of network model to capture the symmetry of graphs:

- John Baez, John Foley, Joseph Moeller, and Blake Pollard, Network Models

Monoids

Now, an example of the object not being present. Consider the category Mon of monoids and monoid homomorphisms, and the full subcategory CMon of commutative monoids. Mon has coproducts, given by the “free product”. If M and N are monoids, then their free product M*N has elements that are “words” of elements from M and N. If two “letters” come from the same monoid in a given word, you can multiply them as in that monoid, and the identity elements of both monoids are identifed with the “empty word”, which then acts as the identity element. Unless one of them is the trivial monoid, M*N is never commutative.

So the coproduct in Mon of two commutative monoids is not in CMon, however, this does not mean that CMon does not have coproducts! Coproducts in CMon are given by products! You can see why this should be true in two different ways. Algebraically, you take the free product M*N, and then mod out by the relation making everything commute. Then in a given word, you can rearrange so that all the letters from M are grouped together, and likewise for N. This is essentially the same as an ordered pair, i.e. an element of MN. The other way to see this is categorical, via universal property. Given two commutative monoids M and N, there are canonical inclusions

and

given by

and

respectively. Then if P is another commutative monoid, and you are given maps

and

, you automatically get a map

given by

. The commutativity of P is necessary for this to be a monoid homomorphism.

This example generalizes to any variety of monoids. A variety of monoids is a full subcategory of the category of monoids which contains all the monoids satisfying a set of defining relations. For example the category of commutative monoids is the variety of monoids which satisfy the relation ab = ba for all pairs of elements a,b. A graphic monoid is one where aba = ab for every pair of elements a,b. The subcategory of graphic monoids is another example of a variety. Notice that the trivial monoid is in every variety.

As with the variety of commutative monoids, the free product of two monoids in a variety is generally not in that variety. However, you can just mod out the free product by the defining relations of the variety. This gives the coproduct in the variety. I used this to generalize the notion of graph products of monoids, which I needed to describe free network models:

- Joseph Moeller, Noncommutative Network Models

Graphs

By “graph”, I mean a directed multigraph. The coproduct in the category of graphs is given by disjoint union. The coproduct in the category of graphs with the same set of vertices X is given by first taking the disjoint union, then identifying the vertices that correspond to the same element of X. Another way of looking at this is that you overlap the two graphs just right so that their vertices line up. This is also the pushout over the obvious inclusions of the graph with X vertices and no edges into the two graphs.

Indexed Categories

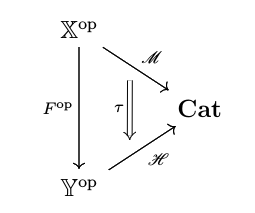

Let be a category. A (strict)

–indexed category is a contravariant functor

. A morphism between two indexed categories,

and

, is a pair (F, τ) where

is a functor, and

is a natural transformation.

We call the category of indexed categories and indexed morphisms ICat. Given two indexed categories and

, their product is given by

, i.e.

.

Consider the subcategory of ICat with only indexed categories of the same base . We call this subcategory

. The product of two

-indexed categories

and

, is given by

where the first part is just duplication, and the rest is the same as before, i.e. .

Fibrations

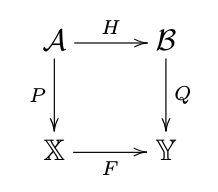

A fibration is a functor with a certain lifting property that I won’t go into detail about now. The category

is called the total category, and

is called the base. A fibred morphism between two fibrations,

and

, is a pair of functors

and

such that the square

commutes, and H respects the lifting property of P and Q. We call the category of fibrations and fibred morphisms Fib.

Given two fibrations and

, their product is given just by the product of functors

.

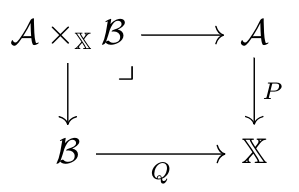

Consider the subcategory of Fib with a fixed base category , and morphisms with trivial base functors. We call this subcategory

. The product of two fixed-base fibrations

and

, is given by pullback:

These last two examples, indexed categories and fibrations, are deeply connected through something called the Grothendieck construction. I plan to talk about this connection in a future blog post. In the following paper, we talk about monoidal variations of this construction.

- Joseph Moeller and Christina Vasilakopoulou, Monoidal Grothendieck Construction

It is also central in the construction of network operads in the other papers I mentioned.

Nice!

LikeLike

Thanks! I wrote this a while ago, and just waited for the Monoidal Grothendieck paper to hit the arxiv to publish it.

LikeLike