Last time, we proved the Lefschetz hyperplane theorem.

Lefschetz Hyperplane Theorem: be a projective variety and

a hyperplane such that

(where

) is smooth. Then

for k≤n-1. (Equivalently,

is an isomorphism for k<n-1, and an injection for k= n-1.

Today we will see an example of how to use this theorem.

Let be a degree d hyperplane. Then Z is the intersection of a hyperplane in

with the image of

under the degree d Veronese embedding (

)

Apply Leftschetz hyperplane theorem with and

. We get

is an isomorphism for k<n-1, and an injection for k=n-1.

Recall where

is degree 2.

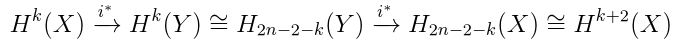

If Z is smooth, then by Poincare Duality (and universal coefficients theorem), for n-1<k ≤2n-2, , which is

when k is even and 0 when k is odd.

Let’s go back to smooth projective, and

. To start, suppose that Y is smooth. Then the composite of

gives an operator on homology which raises the degree by 2. More generally, if projective, consider

Call this the “Lefschetz operator”, call it

. Turns out this is the same operator as the composite above.

Hard Lefschetz Theorem: Let X be a smooth projective variety of dimension n. For any embedding and 0≤i≤n,

is an isomorphism!

Notice: rational coefficients. Also, by Poincare Duality, we already knew , so the juice of the theorem is really that we have a specific isomorphism.

Historical note: We’ll skip the proof, it is hard after all. Grothendieck named the theorem. It was originally proven by Lefschetz in 1924, but nobody could really follow the proof. A better proof was later given by Hodge in 1941, using Hodge theory. Grothendieck and his school later created a cohomology theory for varieties and proved this using ideas similar to those presented by Lefschetz.

Corollary: The map is injective for k<n, and surjective for k ≥ n.

Hence the even (resp odd) Betti numbers

grows as k gets closer to n.

Definition: Say is primitive if

. Let

Corollary: Every $\alpha \in H^k (X; \mathbb Q )$ admits a unique decomposition $\alpha = \sum_r \eta^r \alpha_r$ where $\alpha_r \in H^{k-2r}_{prim} (X; \mathbb Q)$. So .

Finer structure: Poincare Duality gives given by

. P is nondegenerate. With hard Lefschetz, this gives a nondegenerate bilinear form on

; for

,

.

Note when k is even Q is symmetric, when k is odd Q is antisymmetric.

On define

defines a Hermitian form.

Lemma: The Lefschetz decomposition is orthogonal with respect to

.

2 thoughts on “Algebraic Analysis notes Lecture 4 (14 Jan 2019)”