Last time: Hard Lefschetz gives an orthogonal decomposition with respect to a Hermitian form on

defined using the Poincare pairing.

On the other hand, Hodge theory gives a decomposition . So

has an orthogonal decomposition into pieces coming from

.

Hodge-Riemann bilinear relations: The form is positive definite on

.

Products: Fundamental group (or higher homotopy groups) we have . (Co)homology is harder.

Kunneth Formula: for k a field, .

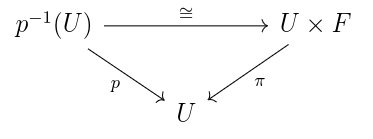

Locally products: A fibre bundle consists of a total space E, a base space B, a fibre F, and a map , such that for any point x in the base B, there is a neighborhood U of x and a homeomorphism such that the following diagram commutes

Question: what is the relationship between and

and

?

Example: is fibred over

with fibre

. Think of

as

and

. Define a map

by

. This is called the Hopf fibration.

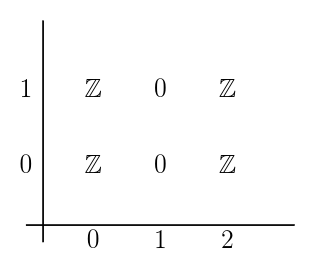

Then we can draw in a grid, spectral sequence

If we take sums along diagonals, i.e. , we get

, but this isn’t exactly the same as

.

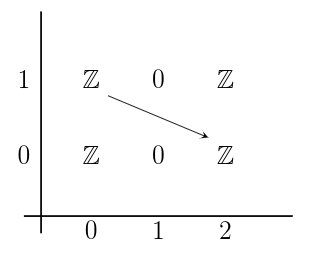

Answer [Leray-Serre]: If B is simply-connected, then there is a spectral sequence .

Roughly, is built out of

“after some cancellations”. The differential cancels out

s on the next page of the spectral sequence:

Theorem [Deligne-Blanchard]: Let be a family of smooth projective varieties. Then the Leray-Serre spectral sequence degenerates at

! There is no cancellation. (Thanks to Daniel Litt for pointing out on Twitter that this is only true for cohomology with coefficients in a field of characteristic 0!)

So for B simply-connected.

The theory of intersection cohomology and perverse sheaves gives a way to simultaneously generalize all of this! Poincare duality, weak & hard Lefschetz, and Hodge-Riemann bilinear relations, intersection cohomology will tell us that some modification of these theorems hold for any projective algebraic variety (not necessarily smooth), and a vast generalization of Deligne’s theorem to arbitrary proper algebraic maps .

To do this we’ll need the theory of sheaves and homological algebra and category theory!

Presheaves

Let X be a topological space. Let Op(X) denote the category with open sets of X for objects and inclusions for morphisms. For a ring k, a presheaf of k-modules on X is a functor . A morphism of presheaves

is a natural transformation. We write PreSh(X; k) for the category of presheaves.

Let’s unpack this definition. F is a rule which assigns to each open subset U of X a k-module F(U), and to each inclusion a homomorphism of k-modules

, called “restriction”.

is called a section of F over U. Notice that functoriality gives

, and if $U \subseteq V \subseteq W$ then

.

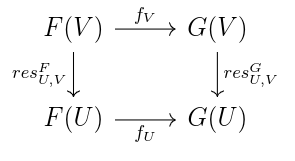

A morphism is a collection of k-module homomorphisms

for each U open in X, such that if U is a subset of V, then the following commutes:

If s is an element of F(V), and U is a subset of V, sometimes we write .

Example: Let M be a k-module. The constant presheaf on X with value M, denoted or

, is given by

for all U open in X, and

for all inclusions

.

We’ll have to continue with sheaves next time.

2 thoughts on “Algebraic Analysis notes Lecture 5 (16 Jan 2019)”