My intention with this blog post is not to teach what a monad is, and it’s not to teach how string diagrams work. I just want to share some strings I drew to represent monoidal monads. This post is the first part of a series of posts where I present a diagrammatic language I used while reading a certain paper. I think it partially answers a question that I’ve had for a while, but I’ll get to that later. Please excuse any minor inconsistencies in my diagrams, like whether red goes over or under blue.

Basic strings

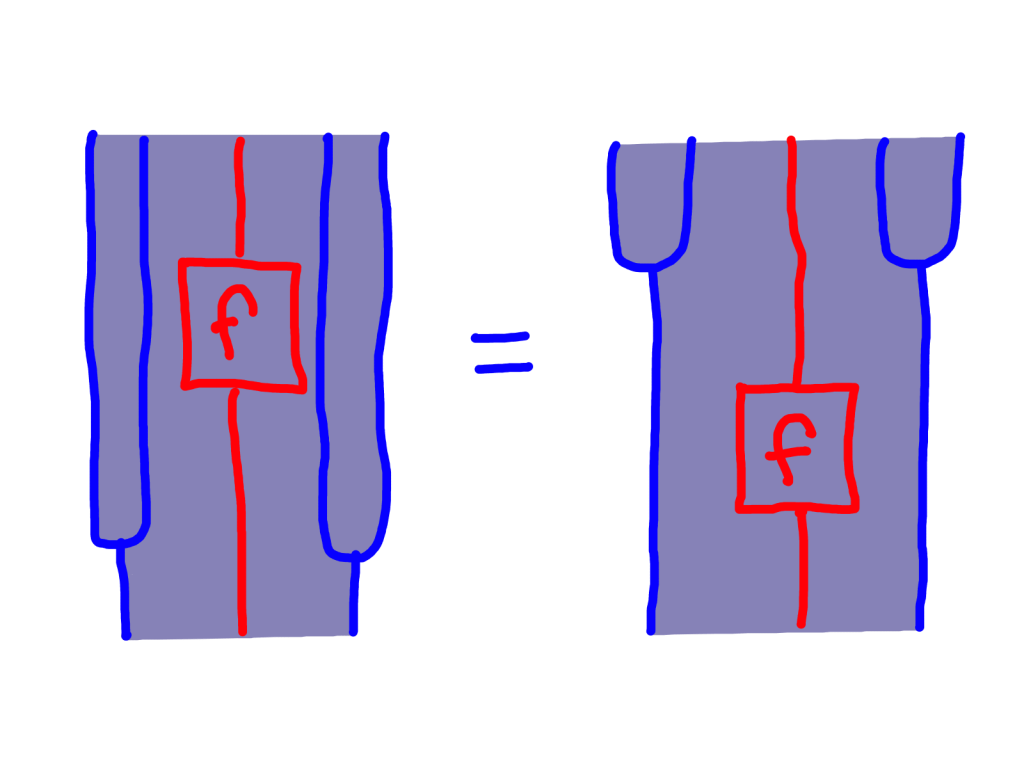

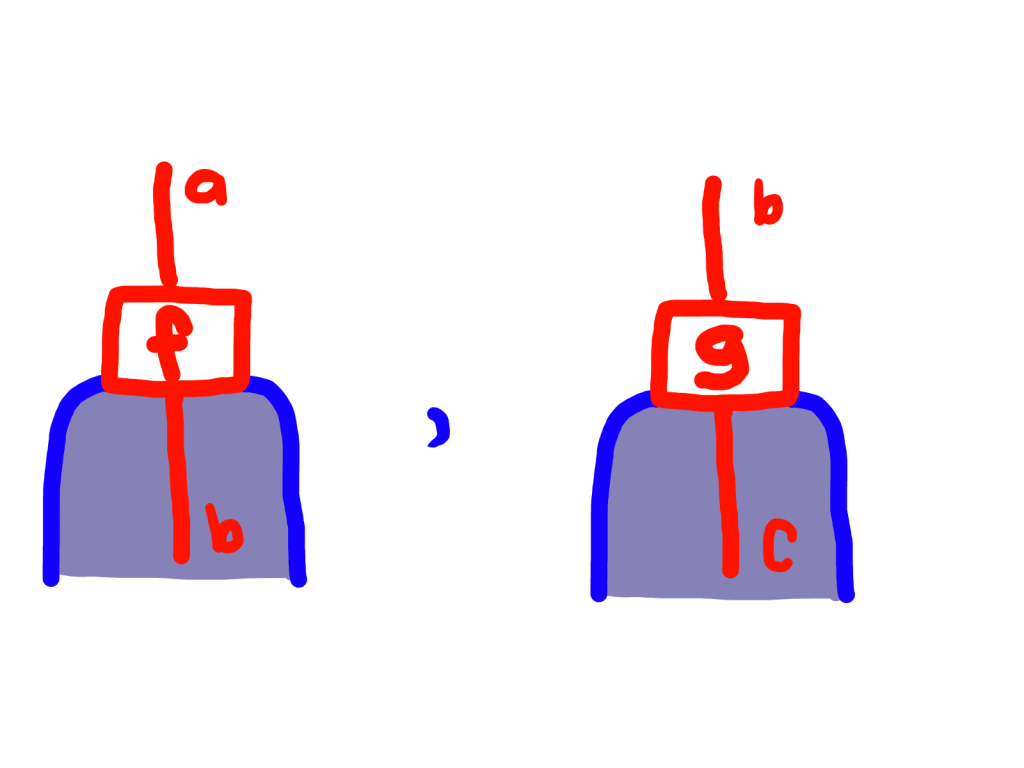

I’m going to assume you’re comfy with string diagrams as a language for reasoning about monoidal categories. For the sake of establishing what my preferences regarding direction and shape, here’s an example of how I would draw a string diagrams representing a morphism f : A⊗B -> C

Monads

You’ve probably seen string diagrams for monads in the catsters videos. I’m going to introduce something a little different here that is better suited to monoidal monads. Here I’ll just present them for ordinary monads.

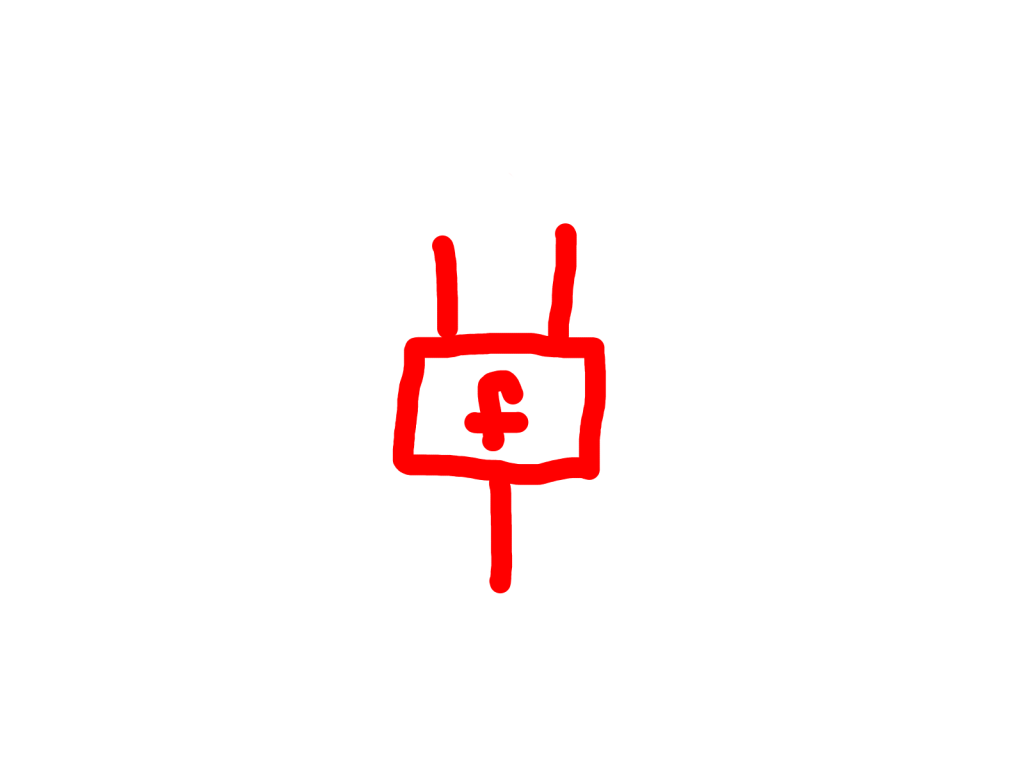

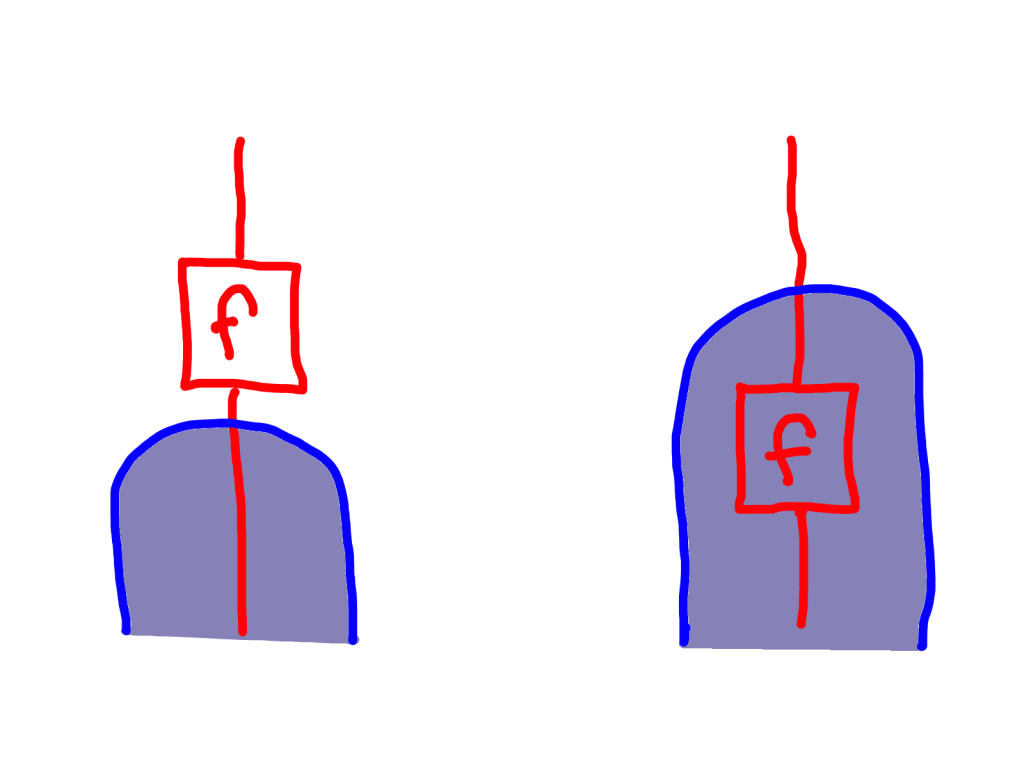

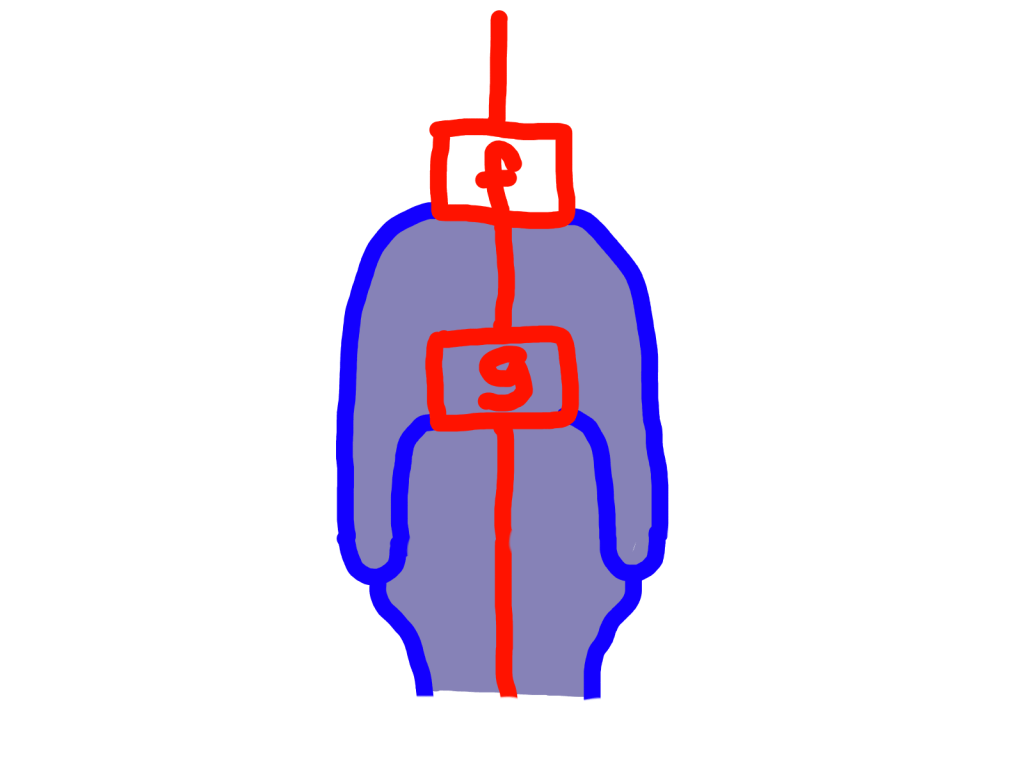

Remember that a monad is an endofunctor T : C -> C which is equipped with the structure of being a monoid object in the category of endofunctors on C where you treat composition as the monoidal structure. The convention of using T for a general monad is convenient, since I’m thinking of it like a tube. The blue lines below are the wall of the tube, and the gray area is the inside of the tube. So the picture below represents Tf.

This could be any endofunctor so far. Notice that we could have nested tubes. We’ll actually have examples of this later. Since I’m only talking about monads, not yet about monoidal monads, the red portion of these diagrams is going to be boring.

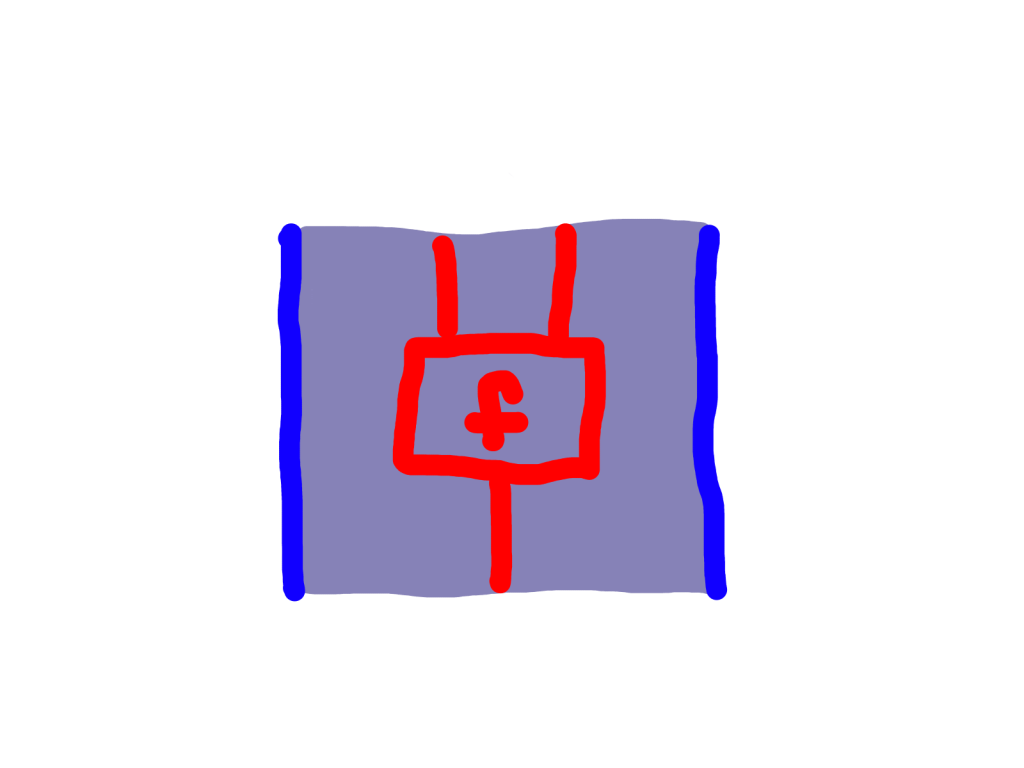

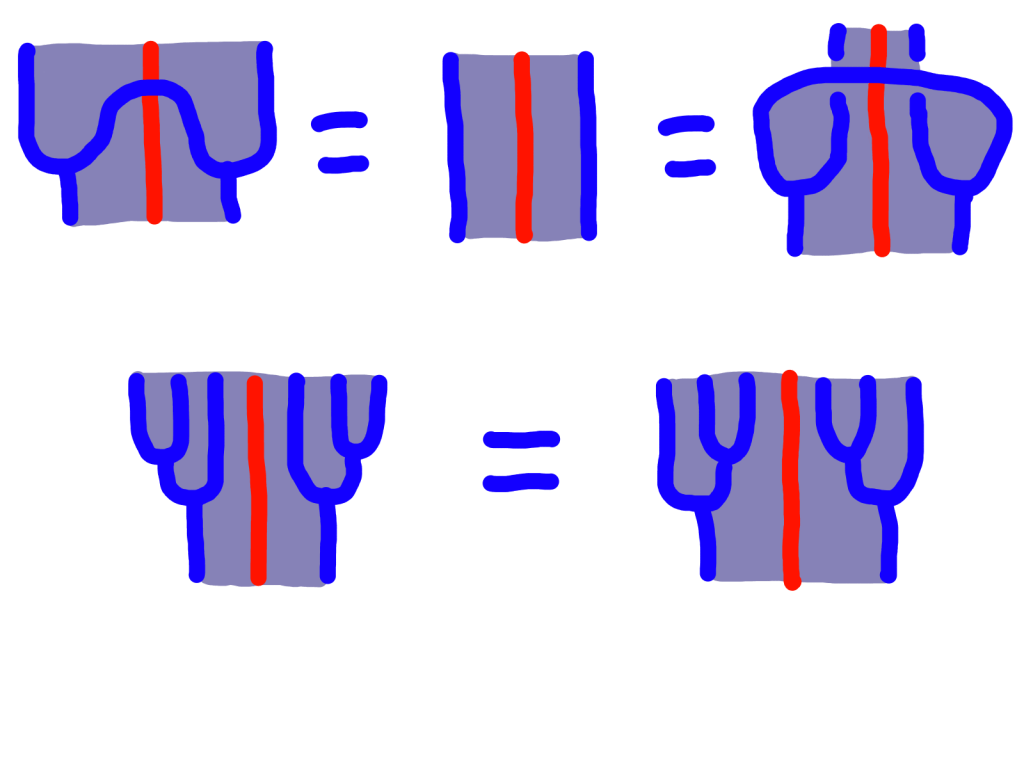

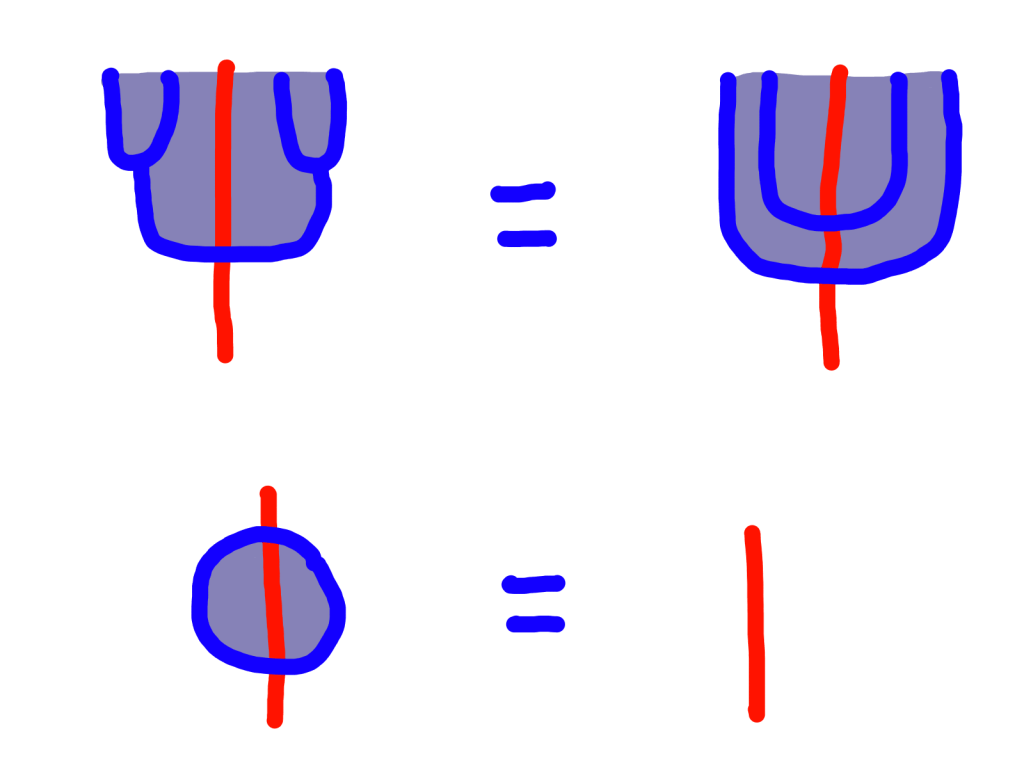

The monad is equipped with a multiplication map TTa->Ta. This should start at the top as a double wall around a red line, and maps down to a single-wall around the line. It’s like getting rid of a tube redundancy. So I’ll draw it like this:

I hope this part isn’t confusing. The merging of two lines into one on both the left and the right are depicting one map. This shouldn’t be confused with two different maps tensored together, as would be the usual way of interpreting this picture in a monoidal category.

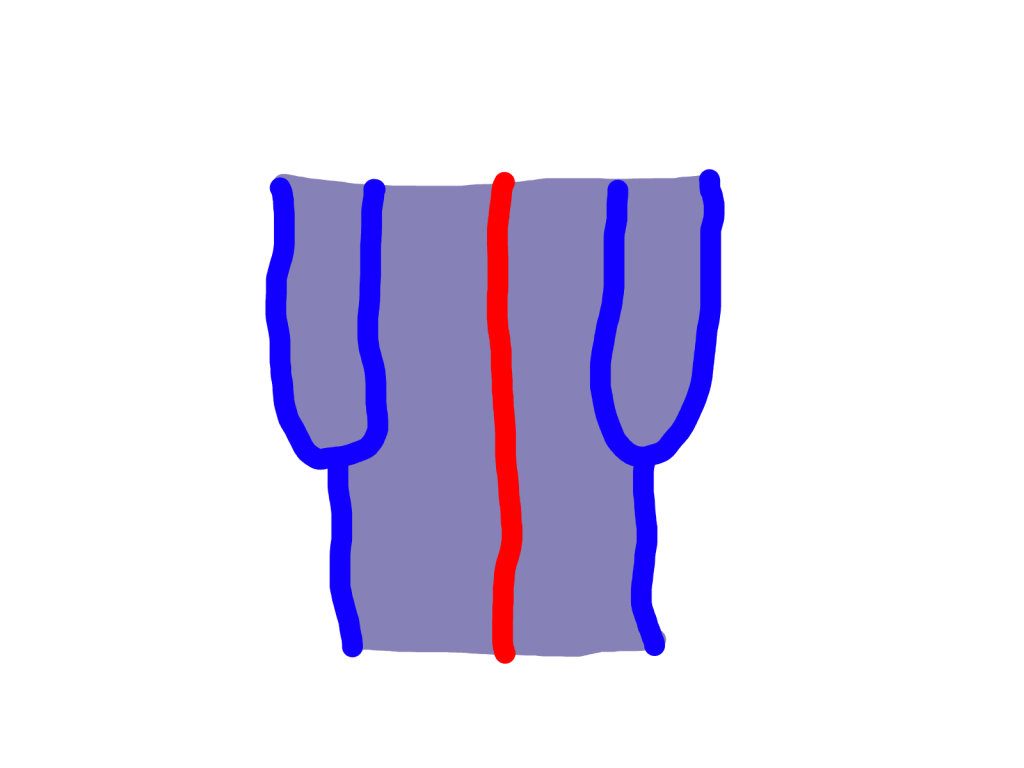

There is also a unit map a -> Ta. I’ll draw this like the object a is breaking into a new tube.

Both of these must be natural as well. A usual with string diagrams, naturality is going to look like sliding disjoint elements past each other. The naturality of multiplication looks like a morphism doesn’t care when a wall collapse happens:

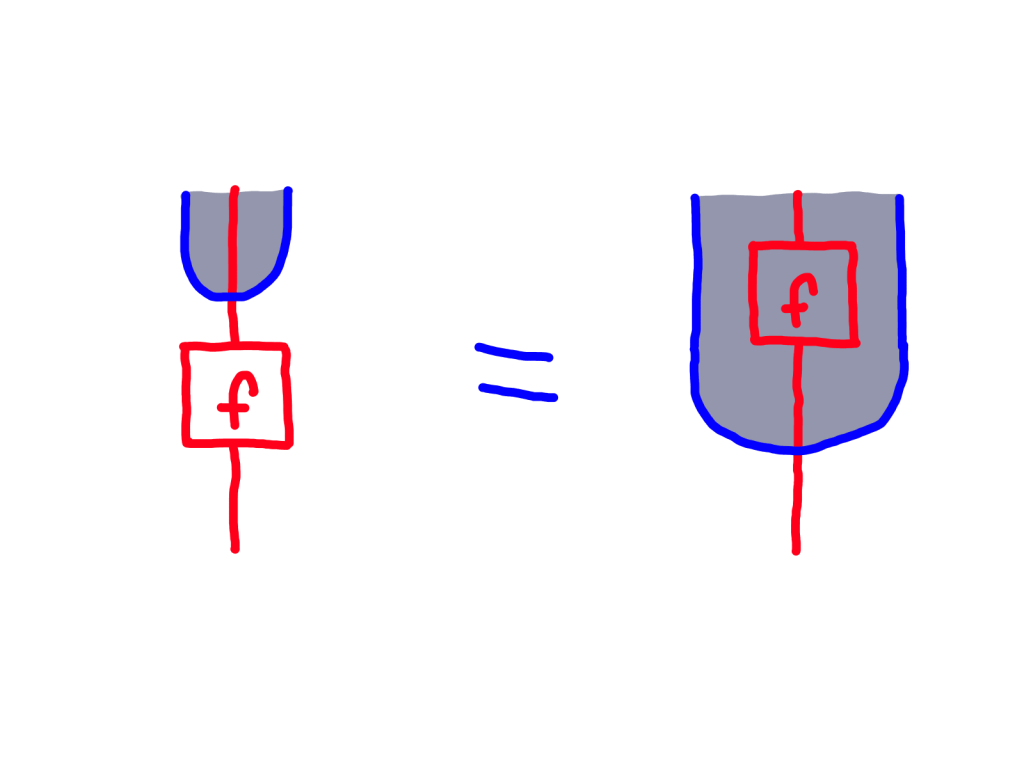

The naturality of the unit looks like a morphism can ride along with an object that is breaking into a new tube:

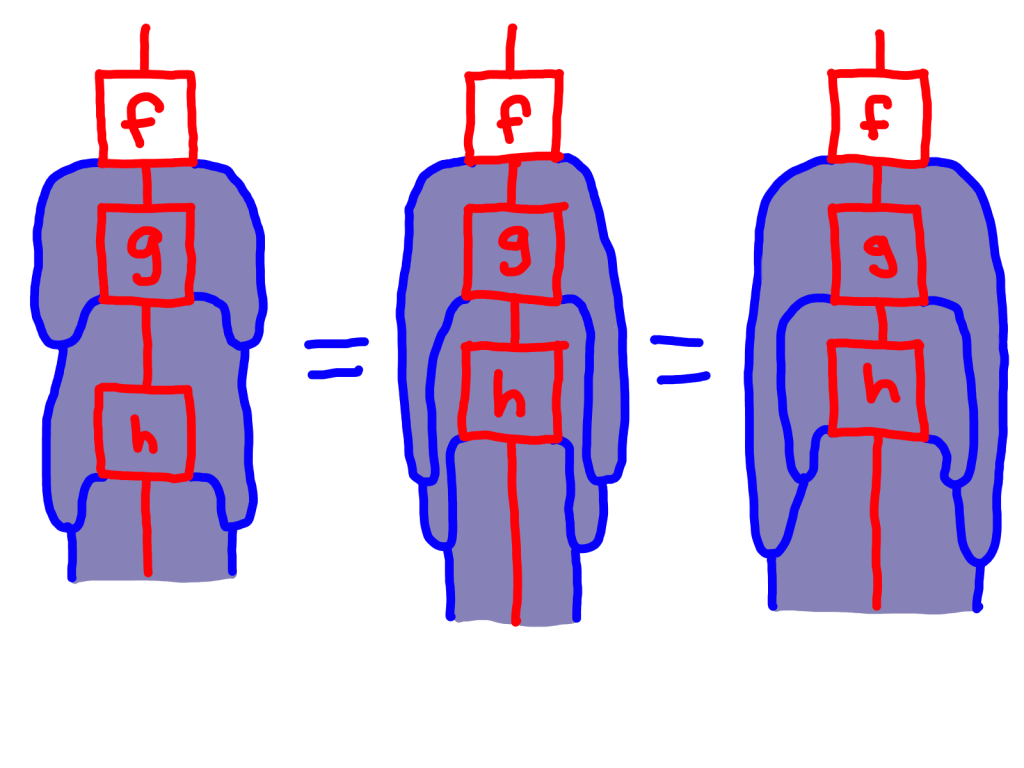

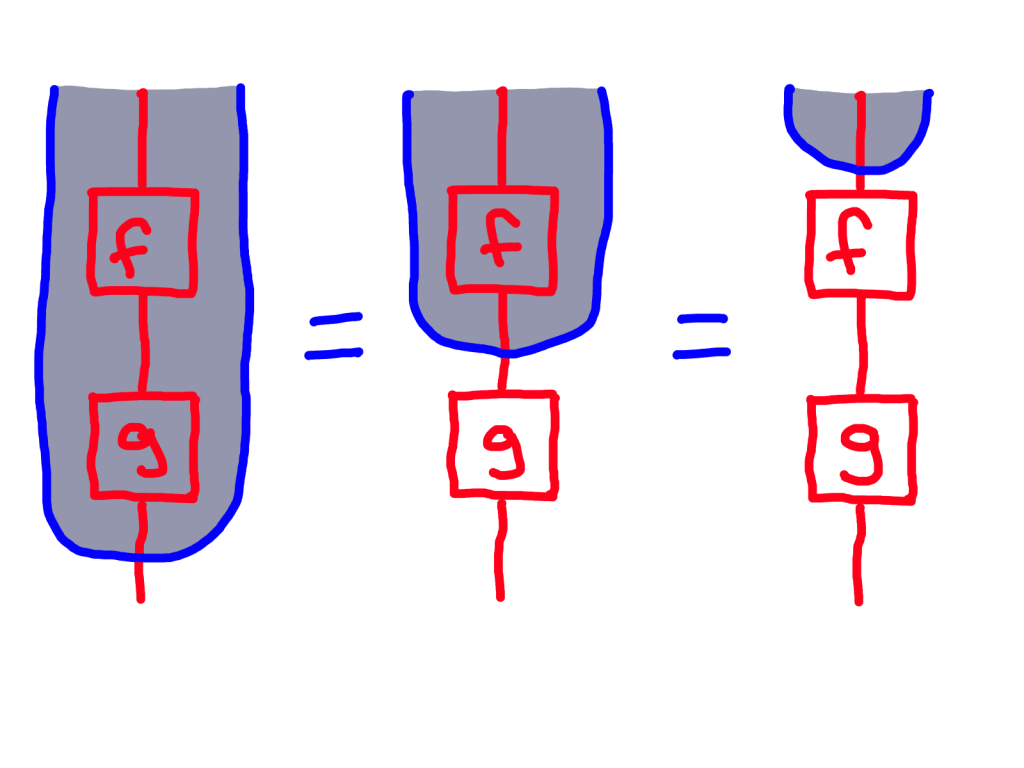

The monad laws look like this:

In the top-left picture, we start with one object in a tube, then we introduce a new tube within that tube, and then we reduce the tube redundancy (i.e. monad multiplication). The top-middle picture is just the identity on an object in a tube. The top-right picture starts with an object in a tube, and then sticks the whole tube into a new tube, and the multiplies. I’ll leave the bottom equation to you to figure out.

Kleisli category

There are two important categories you should think about whenever you have a monad, the Kleisli category and the Eilenberg-Moore category. The objects of the Kleisli category are exactly the objects of the original category, but a Kleisli morphism a -> b is an ordinary morphism of the form f : a -> Tb, which I’ll draw like this:

If we have two composable Kleisli morphisms:

then we define their composite like this:

To be sure that what I’ve said so far gives a category, we would have to check that each object has an identity morphism which is unit with respect to this composition rule, and that this composition rule is associative. Here’s the calculation that it’s associative:

On the left we start with h(gf). The first equation is naturality of multiplication. The second equation is associativity of multiplication. So we end up with (hg)f.

Eilenberg-Moore category

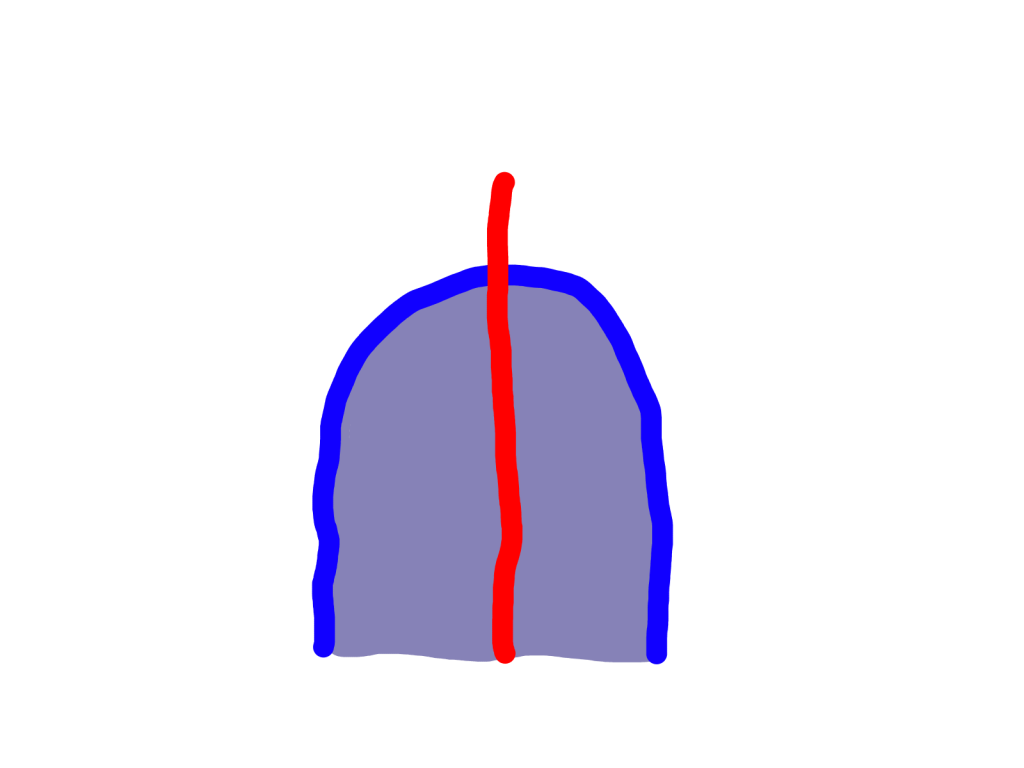

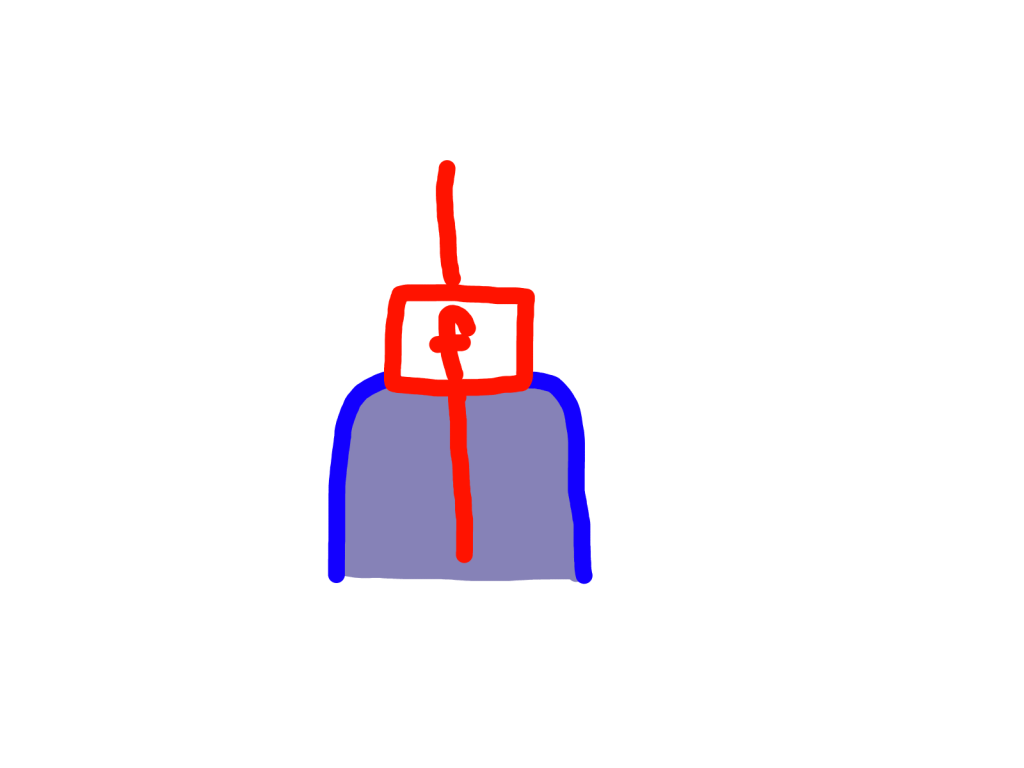

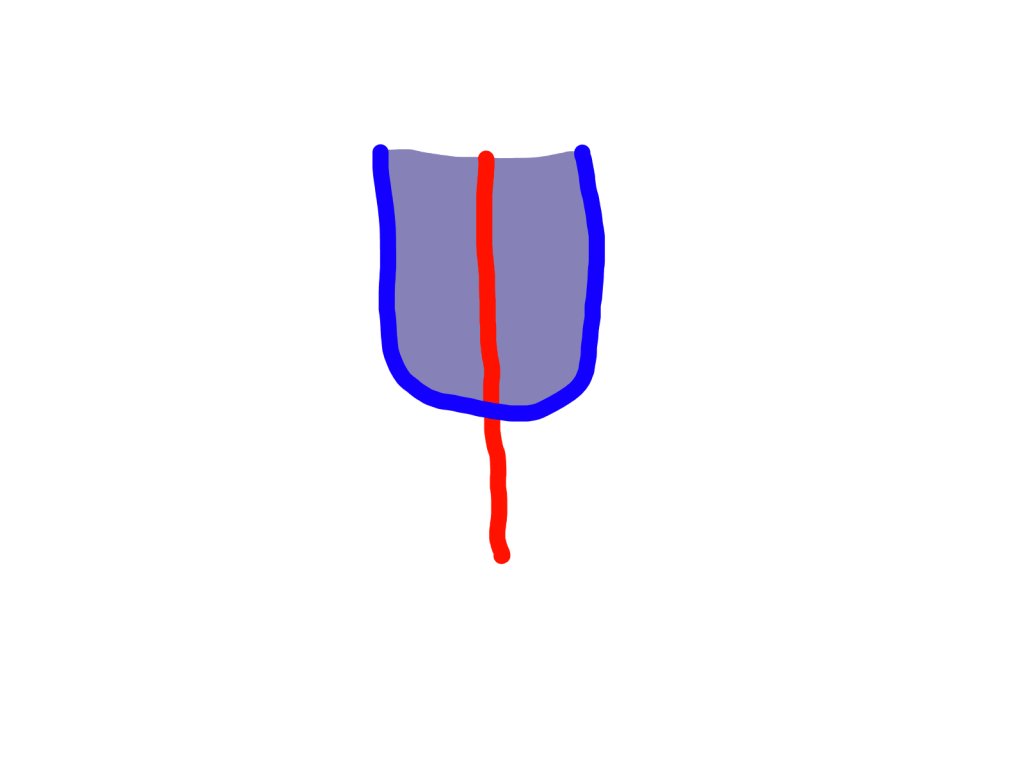

An object of the Eilenberg-Moore category is an object of the original category equipped with a map Ta -> a which satisfies certain relations. I’m drawing it like it’s an object equipped with a get-out-of-tube free card:

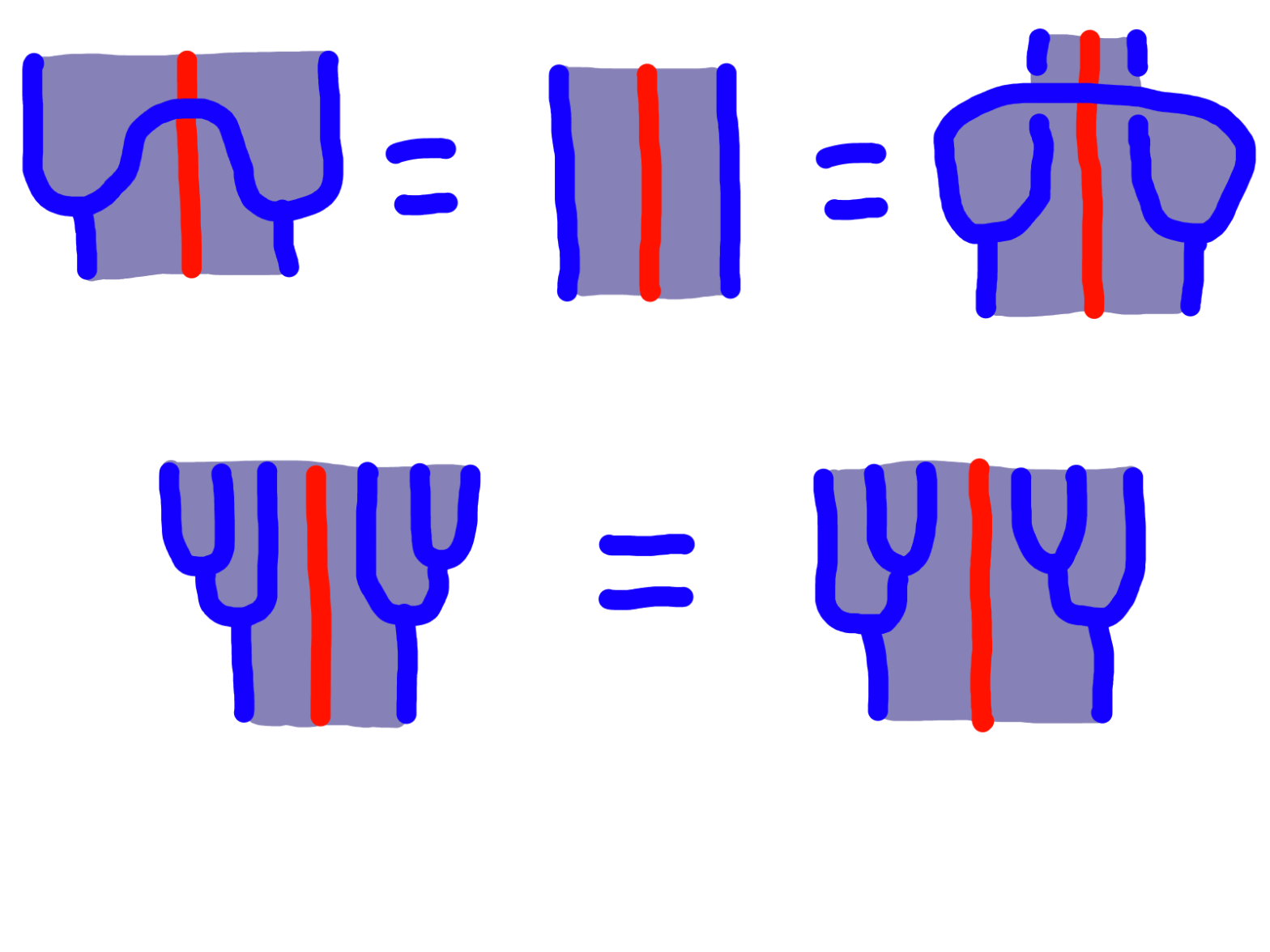

Here are the relations with the monad’s structures that the algebra must satisfy:

The first one is like another redundancy reduction, happening where the red line crosses two blue lines. The second one looks like popping a bubble.

Since we’re equipping objects with extra structure, we’re going to want to restrict our morphisms to those which satisfy certain relations, preserving the structure. This looks like the dual of the naturality of the monad unit. The homomorphism can ride along with the objects that are breaking out of the tube.

Since we’re not changing the morphisms, just restricting them, we don’t need to check associativity of composition. We just need to check that composing two homomorphisms gives a homomorphism.

Ok, that’s all I’ve got for now. In the next post, I show how you can represent monoidal monads in this language, and how you get a monoidal structure on the Kleisli category.

One thought on “A different string presentation of monads”