In this post, I’ll show you the diagrams I used while thinking about monoidal monads. this is building on the diagrams I show you in the first part. There, I showed you the tube-and-string diagrams for just ordinary monads, but I don’t think this is honestly better than other stringy presentations of monads. It’s probably worse. That was just a warmup for presenting monoidal monads, and this is where I think these diagrams are probably actually valuable. The content of what I’ll present now is coming mostly straight out of this paper:

- Seal, Gavin J., Tensors, monads, and actions, Theory and Applications of Categories, Vol. 28, 2013, No. 15, pp 403-434.

Monoidal monads

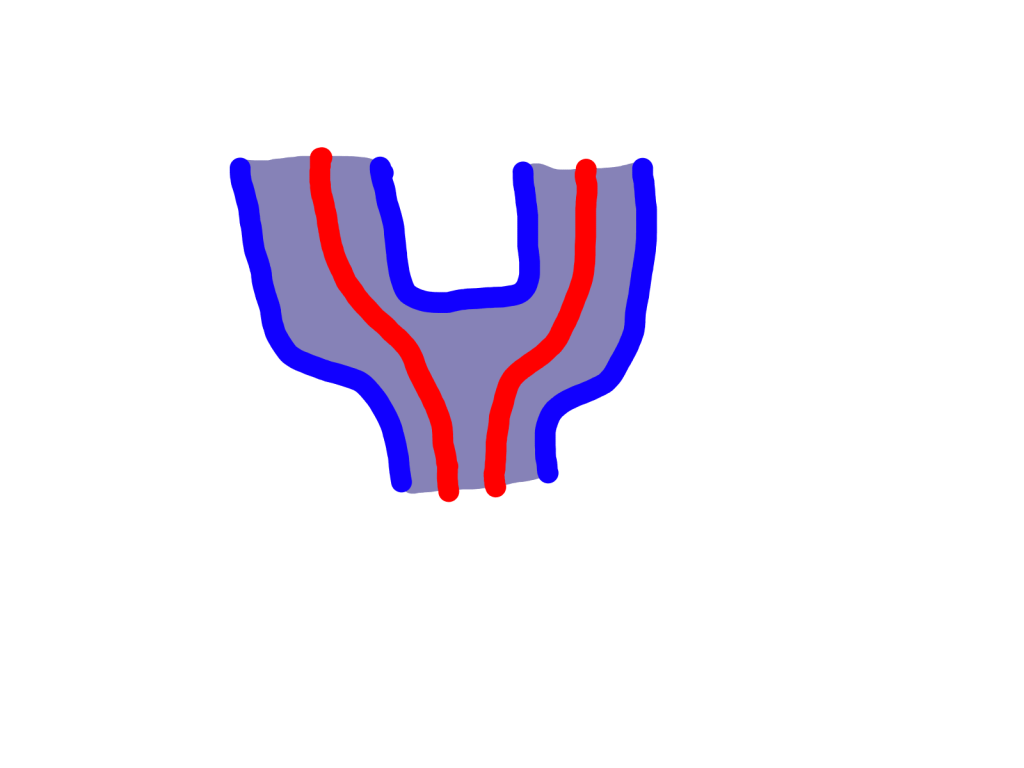

The high-powered way of defining monoidal monad is to say that it’s a monad in the 2-category of monoidal categories, lax monoidal functors, and monoidal natural transformations. But let’s break that down. First of all, a monoidal monad T is going to be a monad on a monoidal category C. Also, the endofunctor part is equipped with the structure of being a lax monoidal functor. This means that it has a natural transformation Ta⊗Tb -> T(a⊗b), which I like to call the “laxator”, and a morphism I -> TI, which I normally don’t give a name to, but I’ll call it the “unit laxator” for now. The interpretation for these is that the laxator lets you merge two tubes:

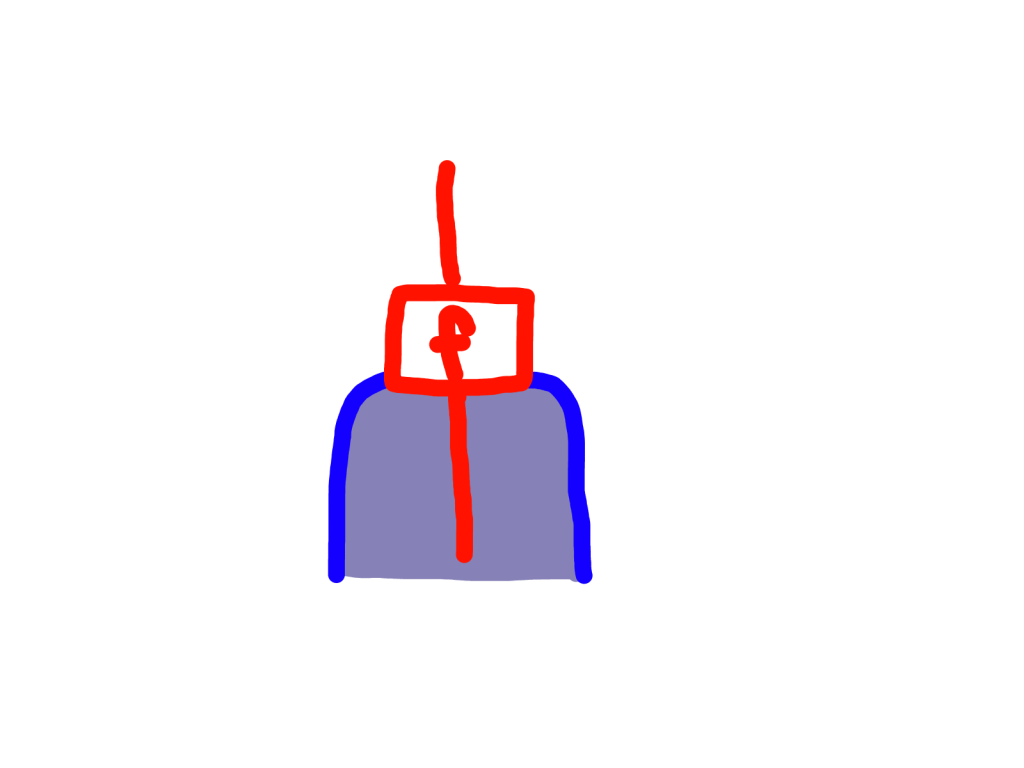

and the unit laxator lets you conjure a new tube out of nowhere:

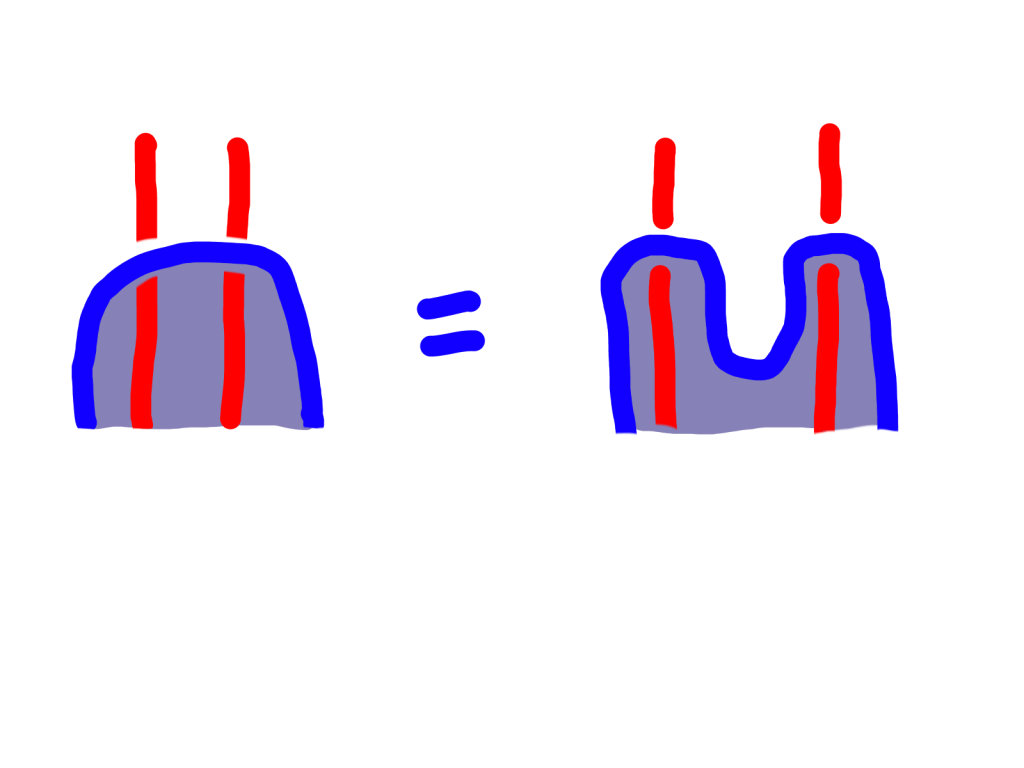

Another thing we get from this definition is that the unit and counit natural transformations must be monoidal natural transformations. For the unit, this gives us two conditions. First, if you have to strings, and they conjure one tube together, this must be the same as if they each conjured a tube separately and then merged them:

The other condition is that the two ways that the unit object can conjure a tube for itself (the unit laxator and the monad unit’s unit object component) are actually the same. So there’s no ambiguity when you draw this:

Further, a symmetric monoidal monad has a symmetric monoidal base category, and a lax symmetric monoidal endofunctor. We don’t need any extra conditions on the unit and counit because a symmetric monoidal natural transformation is not different than a monoidal natural transformation which happens to between lax symmetric monoidal functors. We do get one extra condition from the from the functor being symmetric.

Examples

I’ll mention some examples of monoidal monads for now since it’s a sin not to do so. But I want to dedicate a whole post to exploring the implications for some specific examples.

- The identity functor on any (symmetric) monoidal category is a (symmetric) monoidal monad.

- The free abelian group functor on Set with its cartesian monoidal structure is a symmetric monoidal monad. The laxator

is given by

.

- The power set functor on Set with its cartesian monoidal structure can be made a monad where the monad multiplication is given by union, and can be made a monoidal monad with the laxator

given by taking products of subsets.

- Every functor between categories with finite coproducts is automatically lax monoidal with respect to cocartesian structure. Every monad on a category with finite coproducts is automatically a monoidal monad in this way.

Monoidal structure on the Kleisli category

Last time I should have included something about the left adjoint F : C -> Kl(T). Recall that I said that Kleisli morphisms look like this:

The functor F does nothing to the objects, but given a morphism f : a -> b in C, Ff : Fa -> Fb must be a morphism of C of the form a -> Tb. So let it be this:

Proposition 1.2.2 Given a monad T on a monoidal category C, there is a bijective correspondence between the following data:

- natural transformations Ta⊗Tb -> T(a⊗b) making T a monoidal monad

- monoidal structures on the Kleisli category Kl(T) such that the left adjoint

F : C -> Kl(T) is strict monoidal.

I only want to highlight the construction of the monoidal structure and why the functor F gets to be strict monoidal. Given 1, we define a monoidal structure on Kl(T) as follows. On objects, the tensor product is the same. Given two Kleisli morphisms f and g, define their tensor product to be this:

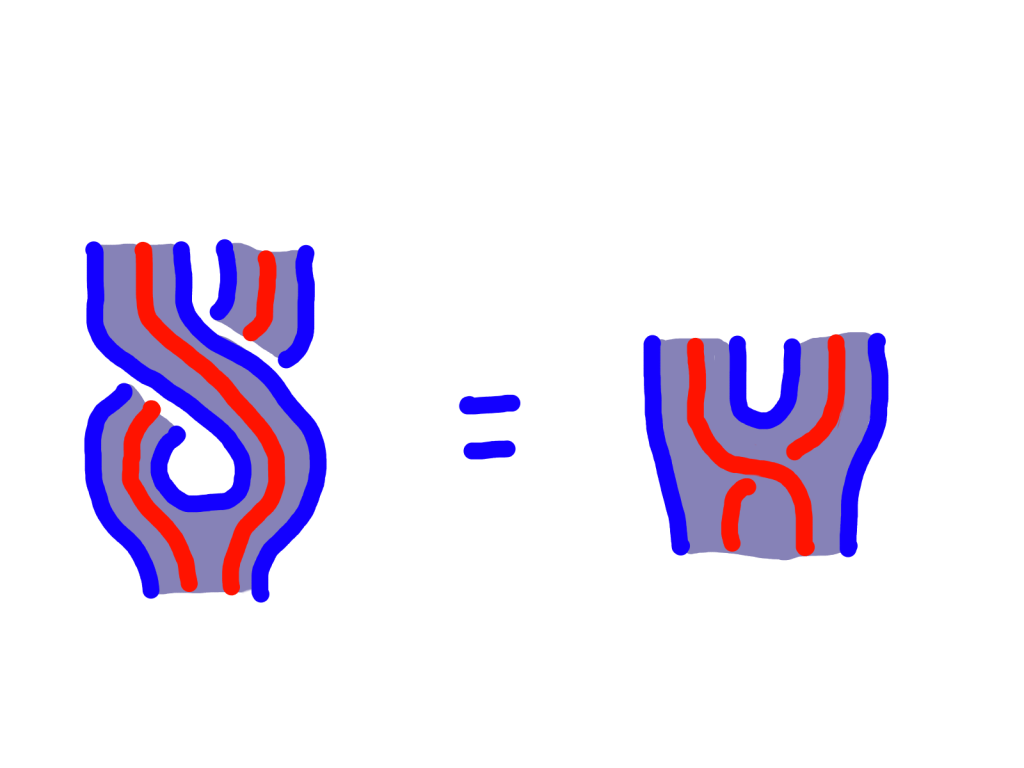

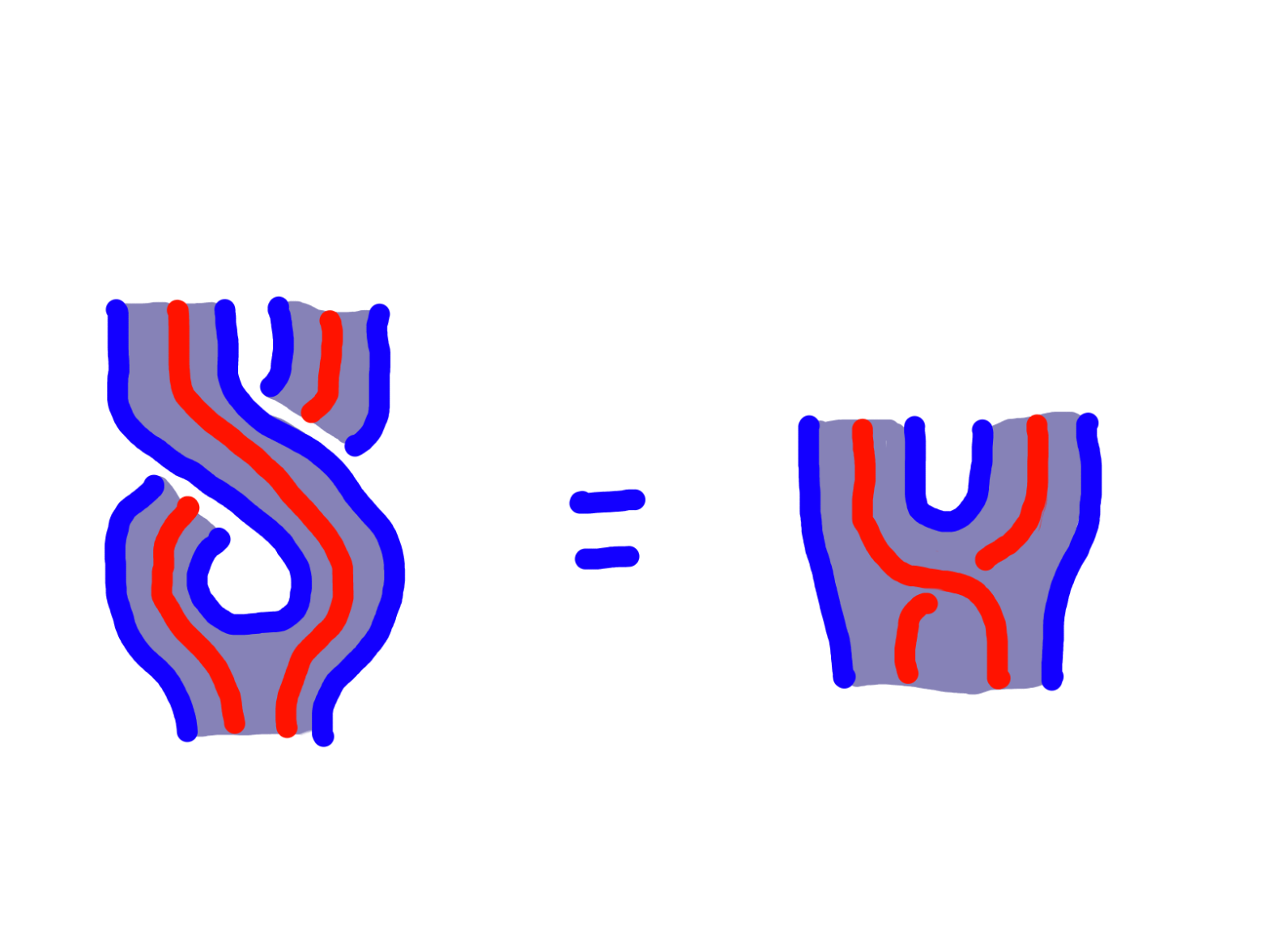

This makes the functor F strict monoidal because Fx⊗Fy = F(x⊗y) = x⊗y, so we can use identity maps in the Kleisli category (which is the monad unit) as our laxator. Then checking this is a natural transformation amounts to checking that the following equation holds:

which is an axiom of T being a monoidal monad.

Next time

I wanted to end this one with the Eilenberg-Moore category and it’s monoidal structure to mirror the first post. There is enough stuff to say about this to justify it’s own post though. I wanted to keep these fairly short anyway.

Hi, Joe!

We´re a group of students at CERN just passing by saying hi. We started watching some relativistic quantum videos pn YT and we ended up in your site.

We really liked your website.

greetings from cern; bye;

00:20_23.09.2024

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1CDnK7RAM9skNvfTaXU-C-I8JnK5wn-LI/view?usp=drive_link

LikeLike